About us

About Isaiyarangam

Music moves the heart. It causes immense joy and draws you into a world of its own. When properly delivered it has the power to charm anyone. But why do we fail to feel this power? Through the recounting and comparison of the history of Carnatic music, and that of its sister music, Hindustani, we hope to uncover the possible causes of the public’s loss in interest in Carnatic music.

It is important to trace the history of our music to identify the causes of concern and situations that arose over the passage of time. In ancient times, folk songs were found to have similar sounds. Upon analysis it was found that there were seven distinct notes. This has now become a universal concept. Upon further analysis it was found that in an octave there were 22 sounds, distinguishable by the human ear. The combination of these notes were loosely structured into puns. Music, when within the boundaries of these combinations, was termed classical music, and all others were folk music. Thus, Carnatic music was born and evolved. It is stated in Silapthikaram that musical competitions were held in which musicians rendered swara bedam (transposing of the existing scale to create a different raga). Carnatic music began with a lot of emphasis on Manodharmam (improvisation). It grew and flourished in South India. When the Moguls took hold of North India, and came to realize the treasure that was in Carnatic music, they wanted something to call their own. Musicians came and learned from the masters of the south, and brought back to the Mogul king, ‘Hindustani music,’ their own version of Carnatic music. In Hindustani music, the entire song is up to personal interpretation.

The song is elaborately decorated with sangathis (same verse with varying tunes). However, in Carnatic music only certain lines in the Charanam are chosen for improvisation, called Niraval, and usually only 3 or 4 times in a concert. Though, there are items such as Pallavi, and Thanam that allow for further, more intricate improvisation, and expression of the artist, the most of the concert is the delivery of pre-rehearsed songs. This is one of many differences between Hindustani and Carnatic music. Hindustani gives importance to the raga and rewards expression, whereas Carnatic music is to the tala structure and rewards technical proficiency. Hindustani has a very flowing, melodious, almost sensual way of delivery. This is one key reason for its mass appeal. Though Hindustani musicians have learned a lot from Carnatic artists, they flourish because of their delicate rendering, and the elasticity of Hindustani. It is no crime to add a foreign swara to beautify a song in Hindustani. Also, the slow incremented tala change also adds flare to concerts, and audience anticipation. In Carnatic music, someone who can perform under such stringent technical constraints, and elaborate tala structures is considered to be of great talent. The rigidity in Carnatic music, though important for technically skilled musicians, loses mass appeal.

Communities that once listened only to Carnatic and Indian cinema songs, soon realized the need for their own music for their own expression. They sought to learn more to gain knowledge technically. They went to India and learned under some of the most proficient musicians of their day adapted it to suit the musical interest and aspirations of their own people. Today they have a distinct, recognized music of their own. Perhaps this is a cause for the low interest we have for classical music. We do not have music that appeals to our own people. We still try to learn to enjoy others and what they have created. We hope to make it ours by listening to it, learning it and excelling in it. The music that is presented to the public now, may not be the one that can evoke the natural, cultural patriotic pride.

Classical fine arts require maturity for understanding and appreciation. Just as one cannot just dive into Shakespeare and love it, one cannot delve into Carnatic music and love it. Its beauties must be taught first and slowly. The listener is taken to the river of Carnatic music through a thick, discouraging forest. In Hindustani music this path is clear, through the well-worn path created by Gazhal. This light, airy music that still includes the virtues of the classical, helps to draw masses into the arts. This simpler version, serves to get people accustomed to the form, and develop a taste for such music and to hunger for more. Its verse is of life and love. Its sweet sounds soothes the soul, intoxicates and makes you yearn for a bit more intricacy, and a bit more, till you reach the level of enjoying classical Hindustani music. This is how one is weaned into a devoted Hindustani classical listener.

We have to create a similar form of music as a gateway to Carnatic music. Today in Toronto, there are more than 1000 students learning Carnatic music. However, the parents who encourage them to learn rarely ever attend concerts that their children are not a part of. Can the reason be the lack of mass appeal of Carnatic music? Can the average person ever learn to love Carnatic music? Is there a bridge between light and classical music? Is it possible to find answers to these nagging questions? The desperate need to bring Carnatic music to all Tamils, especially in Toronto gave rise to the creation of Isaiyarangam, specifically established to explore and find practical means to achieve our goal.

Vision

Propagating a musical structure that is unique to Eelam Tamils.

Mission

Easing the transition of appreciation of light music to classical South Asian music by exposing listeners to key elements of fine art.

Objectives

To foster and preserve our traditional music by:

- Giving listeners who have been over-exposed to harsh Western music a soothing touch of Eastern music

- Combine the artistic vision of poets and musicians to compose unique masterpieces which can be appreciated by the mass public

- Propagate this musical format to places where ever Tamils reside

- Facilitate and encourage the performance of this art for any artist who shows interest

- As music has no boundaries, we must make room for all formats of music and make it available to everyone

Isaiyarangam Performers

Varna Rameswaran

Born to a musical family in Siruvilan Alavetty, he started his musical career at infancy. He learnt miruthangam from R. Vartharajasarma and vocal from his father Kalabooshanam Sri Varna Kulasingam. After graduating from Jaffna University as a vocalist, he was instructing music at the university for 4 years. He has released several CD’s and is presently propagating music through the Varnam Institute.

Arudchelvi Amirthananthan

She is an upcoming artist and learned music in gurukula style from Seetha Ramaiyar and received additional guidance from Mangalam Shankaran. From her tender age, she has exhibited her talent in vocal and consequently participated in All Ceylon Radio and Roopavani. In Canada, she sang in several CDs.

Jeyadevan

A descendant of Abayadev lineage, who was a prevalent artist in Malayala cinema and literature, and with a brother who learnt from Dr. Balamuralikrishna, he was born into a family of immense talent. At the tender age of 8, he started his music lessons from Kalakshethra Matthew for 10 years. He continued advanced training under the tutelage of Nedumankad Sivanandan for another 10 years. He has performed solos as well as accompanied famous artists, such as Thiruvilla Jeyashankar, Vallipatti Subramaniam Dakshinamoorthy, K.J. Jesudas and Chalakudi Narayana Swami. While studying at university, he won a State level competition, receiving the title Kalaprathaba. He has a degree in computer science, and now works as a graphic designer and web designer, while teaching violin at the Varnam Fine Arts Academy in his spare time.

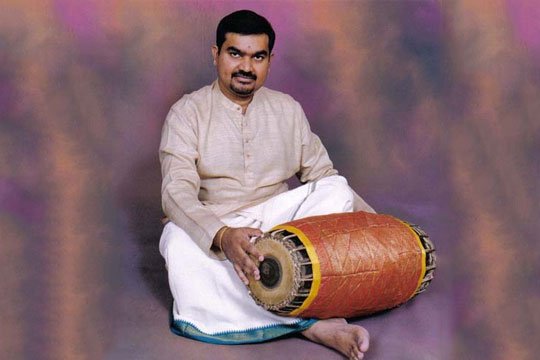

Giritharan Sachithananthan

Started his musical career at a young age from miruthanga vidwan Mylvaganam Kandasamy. Accompanied many artists. He became the disciple miruthanga maestro Thiruchi Shankaran and staged an arangetram under his tutelage. He has played for many artists such as Madurai Sundar, Bhushany Kalyanaraman. He is currently teaching miruthangam and computers at the Tamil Arts Technical Institute.

Gowrishankar Balachandran

Starting his music career at the young age of 8 from Radio Ceylon artist Arumugam Pillai, he relieved further training from Tiruvaroor Bakthavathsalam for 10 years in Thanjavoor Style in gurukula manner. He has played for very well-known artists such as Pathmasri Jesudas, Dr. Ramani, Mathura T. N. Shesagopalan, and Saxophone Kathiri Gopalnath. He has founded Laya Mathura Percussion Arts Center, in which he is Artistic Director and teacher. He has within himself the passion for music, and to explore and experiment with different approaches to music.

Fays Zavahir

The son of K.M. Zavahir, the first composer of Sri Lankan Tamil films, Fiyas started learning classical music, keyboard, mandolin and percussive instruments under the tutelage of his father at a young age. He received advanced training in classical music from Arunthathi Sriranganathan. At 14 he played keyboard for his father’s music group, and started his own band SuperSons at the age of 18. By the age of 24 while working as a composer for Radio Ceylon, he traveled all over the world with B. H. Abdul Hameed, establishing his talent abroad. He has contributed to the music industry with numerous CD releases currently in Toronto, he has a mini-studio where he records his compositions.

Navalan Ilayathamby

Born in Nallur, he started singing in the Rajan orchestra by the age of 10. By the age of 13 he formally started music lessons under the guidance of Mr. Sthambaranathan. He took it upon himself to learn tabla. At the age of 18, he started playing tabla for the Rajan orchestra. When his talent was observed by the famous music composer Kanna, he was approached to and subsequently joining the Kannan band as a vocalist and a tablist. After coming to Canada, he started playing the Tabla, Ocopad, and drums for many bands, but is still receiving advanced training from famous artists.

Kalaivani Rajakumaran

Born in Trincomale, while studying in Shanmuga Mahavidhyalam she gained the appreciation of many scholars. Though she was working towards a degree in Commerce from Jaffna University, her passion remained uncovering and portraying the suffrage of Tamils affected by the civil war and displacement. After coming to Canada, she has writing many poems, drama, and articles captivating the world of Tamil literature.

Kavignar Seran

Son of well know poet Mahakavi Ruthiramoorthy. He is also a well known poet and academic living in Toronto.

Kalaivani Rajakumaran

Born in Trincomale, while studying in Shanmuga Mahavidhyalam she gained the appreciation of many scholars. Though she was working towards a degree in Commerce from Jaffna University, her passion remained uncovering and portraying the suffrage of Tamils affected by the civil war and displacement. After coming to Canada, she has writing many poems, drama, and articles captivating the world of Tamil literature.